MLB’s new rules on the shift prompt recollections of Ted Williams’ greatness

When Major League Baseball announced last week that they’d be implementing new rules in 2023, the late, great Ted Williams’ name popped up all over Twitter.

MLB plans to restrict the shift by mandating that the defense must have at least four players in the infield, with at least two on either side of second base. Their justification for the change:

"“These restrictions are intended to increase the batting average on balls in play, to allow infielders to better showcase their athleticism and to restore more traditional outcomes on batted balls. As of this writing, the league-wide batting average on balls in play of .291 in 2022 is six points lower than in 2012 and 10 points lower than in 2006.”"

People familiar with the history of the game know better.

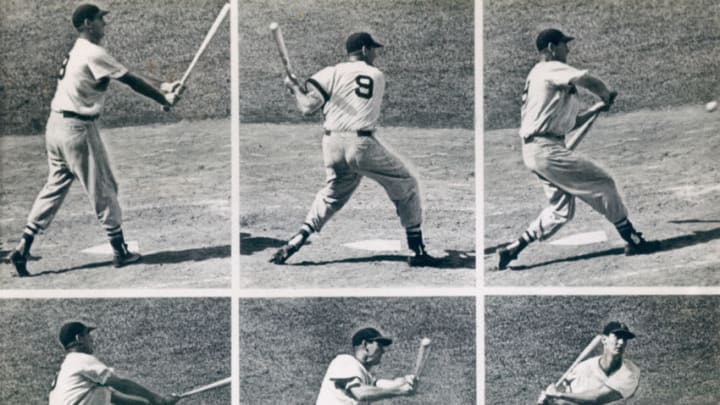

Even though the concept predated his career, the Boston Red Sox legend is inextricably linked to the shift. When Williams returned home from serving in World War II, opposing teams wondered how they might handle the young slugger. Since his debut in 1939, at only 20 years old, he’d hit .356/.481/.642 with 154 doubles, 33 triples, and 127 home runs in his first four seasons. Had there been a Rookie of the Year award back then, he’d have won it. Same goes for Silver Sluggers.

Opposing teams braced for his return. After several years away, he’d be itching to pick up a bat again. How could anyone hope to contain him?

He homered in his first game back. It was as if he’d never left.

On July 14, Cleveland shortstop and manager Lou Boudreau decided to try something new. They were playing a doubleheader with the Sox, and Williams had hit a game-tying grand slam, followed by two more home runs in the first contest, bringing his season total to 26. In mid-July.

In the second game, Williams hit an RBI double in his first at-bat, and Boudreau finally took action. He didn’t invent the shift that day, but he attempted to deploy something rarely seen in the game at that point. He put six guys on the right side of the field.

Williams laughed at the spectacle, the obvious, desperate effort to temper his power.

He did hit directly into the shift, but historians are unclear as to whether that was his way of playing along.

A few months later, on September 13, Williams was back for more. The Sox were in Cleveland, one game away from clinching the American League pennant. With two outs in the first inning, Boudreau shifted everyone but his left-fielder to the right side.

Williams blasted one to League Park’s deep left-center. As the ball traveled over 400 ft without leaving the park, The Kid rounded the bases and slid safely into home. It was the first (and only) inside-the-park home run of his career, and it turned out to be the only run of the contest.

Beating the shift had clinched the pennant.

Today In 1946: Ted Williams beats the “Boudreau Shift” by hitting the first and only inside-the-park HR of his career to help the Boston #RedSox clinch their first AL pennant since 1918! #MLB #Baseball #History pic.twitter.com/8KQDMtqNrG

— Baseball by BSmile (@BSmile) September 13, 2022

Former Cleveland and St. Louis catcher Hank DeBerry could’ve warned Boudreau that the maneuver would be for naught:

"“We used that same defense against Cy [Williams] 25 years ago, and it didn’t work any better than it does today against Ted Williams.”"

That Williams finished his career with a .344/.482/.634 line and 1.116 OPS, 521 home runs, 525 doubles, 1,798 runs scored, and 1,839 RBI, despite missing years of play, indicates as much.

The shift did hurt Williams to an extent. The Cardinals borrowed Boudreau’s maneuver in the 1946 World Series, and Teddy Ballgame, playing through injury, struggled mightily. He even bunted. In the only Fall Classic of his career, he was beaten by the shift.

Still, he finished that season leading all hitters in runs scored, walks and intentional walks (pitchers were terrified to face him), on-base percentage, slugging percentage, and OPS, and led the AL in total bases. He won his first MVP award.

It’s astounding to ponder how much better his career numbers would be if teams hadn’t begun crowding the right side. At his core, he was a pull hitter, and teams found a way to push back, but they could only do so much.

Beginning in 2023, players won’t be able to crowd one side of the field like a spiderweb meant to ensnare the ball. Instead, MLB will continue to play puppet master and pull strings from above, just as they’ve done with the juiced balls, deadened balls, sticky stuff, the three-batter minimum, and countless other changes that toy with their on-field product.

Most hitters don’t come close to Williams. Unfortunately, MLB will make it easier to pretend.

Red Sox legend Fred Lynn has hilarious reaction to new MLB rules

Red Sox legend Fred Lynn posted a funny throwback photo with Carlton Fisk to joke about MLB's new rules on the shift and pitch clocks changing the game.