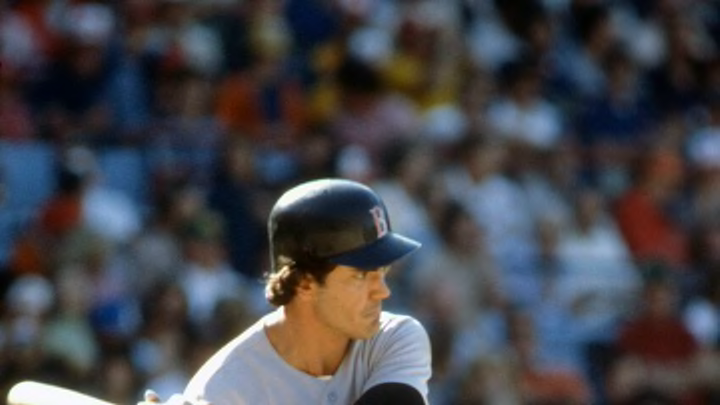

Red Sox SP: Wes Ferrell

4.04. That was Wes Ferrell’s career ERA which, if elected, would be fourteen points higher than any other Hall of Fame pitcher. That one number killed Ferrell’s Hall of Fame chances during his time on the BBWAA ballot and prevented him from being considered by veteran committees. Yet much like Dimaggio, the surface-level statistics don’t tell the whole story of Ferrell’s excellence.

The first thing you need to know about Ferrell’s career is that he played in the most hitter-friendly environment in baseball history. Since the advent of the American League in 1901, 14 of the 18 highest run-scoring seasons occurred from 1920-1939, as well as the 17 highest seasons for batting average.

The pitching statistics of this era suffered dramatically, as only three pitchers during that span posted an ERA under 4.00. If we adjust Ferrell’s ERA to adjust for the run-scoring environment of the time, his total becomes much more reasonable. His ERA+, for which 100 is average, is 116, higher than first-ballot Hall of Famers Steve Carlton and Nolan Ryan.

The other knock-on Ferrell is his relatively short career. After leading the league in innings pitched for three straight seasons, Ferrell made just 32 starts after turning 30, getting rocked to the tune of a 6.07 ERA. This early retirement leaves Ferrell’s counting stats (193 wins, 985 strikeouts) below Hall of Fame standards.

Yet while many players accumulated more wins and struck out more batters over their career than Ferrell, few were more dominant at the peak. From 1929-1936, Ferrell averaged 20 wins a season, finished in the top 10 in ERA seven times, and accumulated 58.7 WAR. His seven-year peak WAR ranks 13th all-time, behind 12 Hall of Famers and Roger Clemens.

What makes Ferrell’s career fascinating is that he was not just a terrific pitcher but an elite hitter as well. No pitcher in baseball history can top his 38 home runs, while his .446 SLG and .797 OPS are also best among pitchers with at least 250 plate appearances. Farrell was such a skilled batsman that he was frequently used as a pinch-hitter, once batting in as many as 75 games in a single season.

Ferrell’s success at the plate only makes it trickier to evaluate his Hall of Fame case. How much weight should you put in his batting value if his primary job was to pitch? Ferrell’s 48.8 pitching WAR is well below the Hall of Fame standard but add in the additional 11.3 WAR he accumulated as a batter, and he is right on the edge.

Ferrell’s resume is undoubtedly unique but far from insignificant. No player in history other than Babe Ruth possessed the combination of skills that Ferrell brought to the table. Every Hall of Famer is built differently, and there is no one route to Cooperstown.

Even if his cumulative pitcher numbers fall short of Hall of Fame standards, Ferrell’s dominant peak on the mound and unmatched offensive production should earn him another look from the Veteran’s Committee.