The Boston Red Sox had a chance to sign a teenage Willie Mays before anyone else did, but the internal machinations of their dark past prevented it.

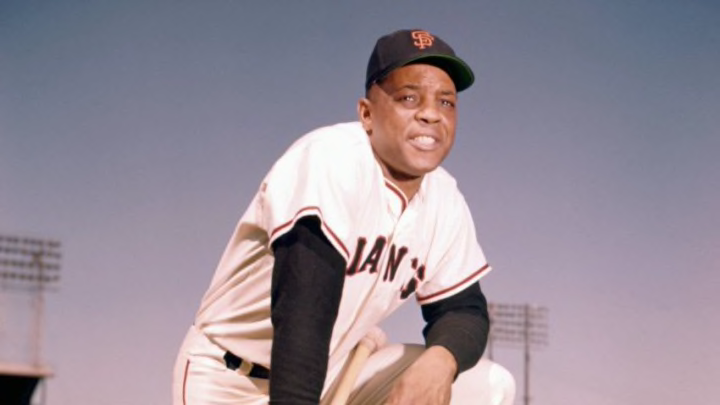

Few people would argue that Willie Mays was one of the greatest baseball players of all time. His career accomplishments are too numerous to mention here and he was one of the most iconic players of the 1950s and 1960s. Mays played all but the final season and a half of his 22 year career with the New York/San Francisco Giants and is forever identified with the team, but for a brief moment there was a very real chance he could have started his career with the Boston Red Sox.

The Say Hey Kid turned 89 years old last week and has been giving interviews to help promote his new book titled “24: Life Stories and Lessons from the Say Hey Kid.” The book is Mays looking back on his life and career as well as some stories from famous figures who share their own memories of Willie. One of the stories Mays shares, though, should ring a bell with Red Sox fans steeped in the team’s shameful racial history.

As Mays recounts in the book, when he was a teenager playing for the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro Leagues, the Red Sox had a minor league team that shared a field with them. Multiple teams scouted Mays, including the Red Sox, and former Sox scout George Digby actually had a deal in place to purchase Mays’ contract for $4500 in 1950 before it was scuttled by the front office.

"“I had Willie Mays bought for $4500,” Digby told me when I interviewed him in 2005. “I called up the Red Sox. I said, ‘I got Willie Mays. He’ll break the color line.'”“The owner of the Black Barons had told us we could have Mays for $4500. I said, ‘I’ll be back to you by tomorrow.’ Glennon had asked me, ‘What do you think?’ I said, ‘I think he’s a big leaguer.’ We could have had Mays in center and [Ted] Williams in left.”"

Instead, as Digby recounted, Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey and General Manager Joe Cronin passed on Mays, saying they “already had made up their minds they weren’t going to take any black players.” Indeed, the Red Sox had years earlier passed on signing Jackie Robinson, with then General Manager Eddie Collins and Yawkey passing for the same shameful reason.

Indeed, the Red Sox would become the final team to integrate when they called Pumpsie Green up from the minor leagues in 1959, a whopping twelve years after Robinson broke the color barrier in baseball. This is ostensibly a huge reason why the Red Sox were so bad throughout the 1950s as they missed out on a huge pool of talented players from which to bolster their club simply because of their institutionalized racial policy at the time.

More from Red Sox History

- Two notable Red Sox anniversaries highlight current organizational failures

- Contemporary Era Committee doesn’t elect any former Red Sox to Hall of Fame

- Johnny Damon calls Red Sox out, reveals hilarious way he skirted Yankees’ grooming policy

- Remembering the best Red Sox Thanksgiving ever

- Red Sox World Series legends headline 2023 Hall of Fame ballot

Among the biggest of those “what ifs” has to be Mays, who was practically dropped into their lap for a pittance. The Red Sox had the inside track due to sharing a field with his team, Digby and other scouts all raved about his talent, and all had him pegged as a no-doubt big leaguer within a couple of years. The Red Sox in theory could have had Ted Williams, Willie Mays, and Jackie Robinson anchoring the team in the 1950s but instead passed on the latter two for the worst of reasons.

Mays doesn’t seem to have forgotten it, mentioning in a recent interview that “they (the Red Sox) had me easy” had they simply bought his contract. Mays then recounted how when he went to the second All-Star game of the season in 1961 at Fenway Park (from 1959 to 1962 the league held two All-Star games per season) the Boston media tried to get him to say that he wished he were a Red Sox.

Instead, Mays said he replied “No, I’ll go where they paid my family.” That place could have very easily been Boston had ownership and the front office had a more open mind and less prejudice than they did.